3 Making a sourdough starter

In this chapter you will learn how to make your own sourdough starter, but before doing so you will quickly learn about baker’s math. Don’t worry, it’s a very simple way to write a recipe which is cleaner and more scalable. Once you get the hang of it you will want to write every recipe this way. You will learn to understand the signs indicating your starter’s readiness, as well as how to prepare your starter for long-term storage.

3.1 Baker’s math🔗

In a large bakery, a determining factor is how much flour you have at hand. Based on the amount of flour you have, you can calculate how many loaves or buns you can make. To make it easy for bakers, the quantity of each ingredient is calculated as a percentage based on how much flour you have. Let me demonstrate this with a small example from a pizzeria. In the morning you check and you realize you have around 1 kg of flour. Your default recipe calls for around 600 g of water. That would be a typical pizza dough, not too dry but also not too wet. Then you would be using around 20 g of salt and around 100 g of sourdough starter.1 The next day you suddenly have 1.4 kg of flour at hand and thus can make more pizza dough. What do you do? Do you multiply all the ingredients by 1.4? Yes you could, but there is an easier way. This is where baker’s math comes in handy. Let’s look at the default recipe with baker’s math and then adjust it for the 1.4 kg flour quantity.

|

|

|

||||||

| Flour | 1000 g | 100 % | 1000 g of 1000 g | is | 100 % | |||

| Water | 600 g | 60 % | 600 g of 1000 g | is | 60 % | |||

| Sourdough starter | 100 g | 10 % | 100 g of 1000 g | is | 10 % | |||

| Salt | 20 g | 2 % | 20 g of 1000 g | is | 2 % |

Note how each of the ingredients is calculated as a percentage based on the flour. The 100 % is the baseline and represents the absolute amount of flour that you have at hand. In this case that’s 1000 g (1 kg).

Now let’s go back to our example and adjust the flour, as we have more flour available the next day. As mentioned the next day we have 1.4 kg at hand (1400 g).

|

|

|

|||||||

| Flour | 100 % | 1400 | × | 1 | = | 1400 g | |||

| Water | 60 % | 1400 | × | 0.6 | = | 840 g | |||

| Sourdough starter | 10 % | 1400 | × | 0.1 | = | 140 g | |||

| Salt | 2 % | 1400 | × | 0.02 | = | 28 g | |||

For each ingredient we calculate the percentage based on the flour available (1400 g). So for the water we calculate 60 % based on 1400. Open up your calculator and type in 1400 × 0.6 and you have the exact value in grams that you should be using. For the second day, that is 840 g . Proceed to do the same thing for all the other ingredients and you will know your recipe.

Let’s say you would want to use 50 kg of flour the next day. What would you do? You would simply proceed to calculate the percentages one more time. I like this way of writing recipes a lot. Imagine you wanted to make some pasta. You would like to know how much sauce you should be making. Now rather than making a recipe just for you, a hungry family arrives. You are tasked with making pasta for 20 people. How would you calculate the amount of sauce you need? You go to the internet and check a recipe and then are completely lost when trying to scale it up.

3.2 The process of making a starter🔗

Making a sourdough starter is very easy, all you need is a little bit of patience. It is in fact so easy that it can be summarized in a simple Flowchart 3.1 The flour you should use to bootstrap your starter is ideally a whole flour. You could use whole-wheat, whole-rye, whole-spelt or any other flour you have. In fact gluten free flours such as rice or corn would also work. Don’t worry, you can always change the flour later. Use whatever whole flour you already have at hand.

Your flour is contaminated with millions of microbes. As explained before in the chapter about wild yeast and bacteria, these microbes live on the surface of the plant. That’s why a whole flour works better because you have more natural contamination from the microbes you are trying to cultivate in your starter. More of them live on the hull compared to the endophytes living in the grain.

Start by measuring approximately 50 g of both flour and water. The measurements don’t have to be exact; you can use less or more, or just eyeball the proportions. These values are just shown as a reference.

Don’t use chlorinated water when setting up your starter. Ideally, you should use bottled water. In certain regions like Germany, tap water is perfectly fine. Chlorine is added to water as a disinfectant to kill microorganisms; you will not be able to grow a starter with chlorinated water.

In this process, the hydration of your starter is 100 %. This means you’re using equal amount of flour and water. Stir everything together so that all the flour is properly hydrated. This step activates the microbial spores in your mixture, drawing them out of hibernation and reviving them. Finally, cover your mixture but make sure the covering is not airtight. You still want some gas exchange to be possible. I like to use a glass and place another inverted one on top.

Now an epic battle begins, as visualized in Figure 3.2. In one study [4] scientists have identified more than 150 different yeast species living on a single leaf of a plant. All of the different yeasts and bacteria are trying to get the upper hand in this battle. Other pathogens such as mold are also being activated as we added water. Only the strongest most adaptable microorganisms will survive.

By adding water to the flour the starches start to degrade. The seedling tries to sprout but it no longer can. Essential for this process is the amylase enzyme. The compact starch is broken down to more digestible sugars to fuel plant growth. Glucose is what the plant needs in order to grow. The microorganisms that survive this frenzy are adapted to consuming glucose.

Luckily for us bakers, the yeast and bacteria know very well how to metabolize glucose. This is what they have been fed in the wild by the plants. By forming patches on the leaf and protecting the plant from pathogens they received glucose in return for their services. Each of the microbes tries to defeat the other by consuming the food fastest, producing agents to inhibit food uptake by others or by producing bactericides and/or fungicides. This early stage of the starter is very interesting as more research could possibly reveal new fungicides or antibiotics.

Depending on where your flour is from, the starting microbes of your starter might be different than the ones from another starter. Some people have also reported how the microbes from your hand or air can influence your starter’s microorganisms. This makes sense to a certain extent. Your hand’s microbes might be good at fermenting your sweat, but probably not so good at metabolizing glucose. The contamination of your hands or air might play a minor role in the initial epic battle. But only the fittest microbes fitting the sourdough’s niche are going to survive.

This means the microorganisms knowing how to convert maltose or glucose will have the upper hand. Or the microbes fermenting the waste of the other microbes. Ethanol created by the yeast is metabolized by the bacteria in your sourdough. That’s why a sourdough has no alcohol. I can confirm the role of aerial contamination to a certain extent, when setting up a new sourdough starter the whole process is quite quick for me. After a few days my new starter seems to be quite alive already. This might be due to previous contamination of flour fermenting microbes in my kitchen.

Wait for around 24 hours and observe what happens to your starter. You might see some early signs of fermentation already. Use your nose to smell the dough. Look for bubbles in the dough. Your dough might already have increased in size a little bit. Whatever you see and notice is a sign of the first battle.

Some microbes have already been outperformed. Others have won the first battle. After around 24 hours most of the starch has been broken down and your microbes are hungry for additional sugars. With a spoon take around 10 g from the previous day’s mixture and place it in a new container. Again—you could also simply eye ball all the quantities. It does not matter that much. Mix the 10 g from the previous day with another 50 g of flour and 50 g of water.

Note the ratio of 1:5. I very often use 1 part of old culture with 5 parts of flour and 5 parts of water. This is also very often the same ratio I use when making a dough. A dough is nothing else than a giant sourdough starter with slightly different properties. I’d always be using around 100 g to 200 g of starter for around 1000 g of flour (baker’s math: 10 % to 20 % ).

Homogenize your new mixture again with a spoon. Then cover the mix again with a glass or a lid. If you notice the top of your mixture dries out a lot consider using another cover. The dried-out parts will be composted by more adapted microbes such as mold. In many user reports, I saw mold being able to damage the starter when the starter itself dried out a lot.

You will still have some mixture left from your first day. As this contains possibly dangerous pathogens that have been activated make sure you discard this mixture. A rule of thumb is to begin keeping the discard, the moment you made your first successful bread. At that point your discard is long-fermented flour that is an excellent addon used to make crackers, pancakes or delicious hearty sandwich bread…I also frequently dry it and use it as a rolling agent for pizzas that I am making.2

You should hopefully again see some bubbles, the starter increasing in size and/or the starter changing its smell. Some people give up after the second or third day, because the signs might no longer be as dominant as they were on day one. The reason for this lies in only a few select microbes starting to take over the whole sourdough starter. The most adaptable ones are going to win, they are very small in quantity and will grow in population with each subsequent feeding. Even if you see no signs of activity directly, do not worry, there is activity in your starter at a microscopic level.

24 hours later again we will repeat the same thing again until we see that our sourdough starter is active. More on that in the next section of this book.

3.3 Determining starter readiness🔗

For some people the whole process of setting up a starter takes only 4 days. For others it can take 7 days, for some even 20 days. This depends on several factors including how good your wild microbes are at fermenting flour. Generally speaking, with each feeding your starter becomes more adapted to its environment. Your starter will become better at fermenting flour. That’s why a very old and mature starter you receive from a friend might be stronger than your own starter initially. Over time your sourdough starter will catch up. Similarly, modern baking yeast has been isolated like this from century old sourdough starters.

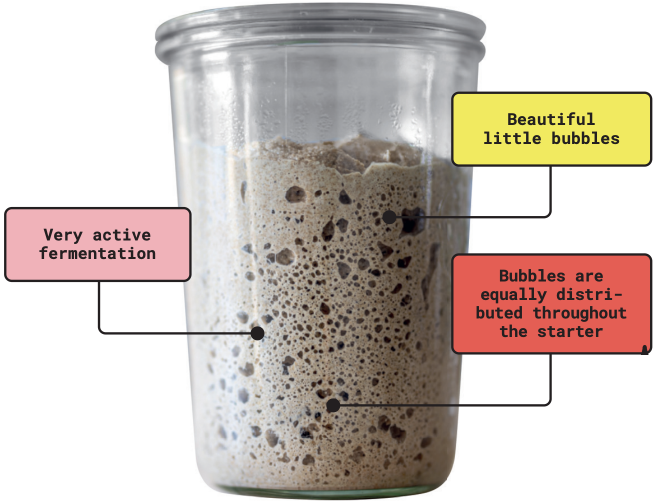

The key sign to look at is bubbles that you see in your starter jar. This is a sign that the yeast is metabolizing your dough and creates CO. The CO is trapped in your dough matrix and then visualized on the edges of the container.

Also note the size increase of your dough. The amount the dough increases in size is irrelevant. Some bakers claim it doubles, triples or quadruples. The amount of size increase depends on your microbes, but also on the flour that you use to make the starter. Wheat flour contains more gluten and will thus result in a larger size increase. At the same time the microbes are probably not more active compared to when living in rye sourdough. You could only argue that wheat microbes might be better at breaking down gluten compared to rye microbes. That’s one of the reasons why I decided to change the flour of my sourdough starter quite often. I had hoped to create an all-around starter that can ferment all sorts of different flour.3

Your nose is also a great tool to determine starter readiness. Depending on your starter’s microbiome you should notice either the smell of lactic acid or acetic acid. Lactic acid has dairy yogurty notes. The acetic acid has very strong pungent vinegary notes. Some describe the smell as glue or acetone. Combining the visual clues of size increase and pockets plus the smell is the best way to determine starter readiness.

In rare events your flour might be treated and prevent microbe growth. This can happen if the flour is not organic and a lot of biochemical agents have been used by the farmer. In that case simply try again with different flour. Ten days is a good period of time to wait before trying again.

Another methodology used by some bakers is the so called float test. The idea is to take a piece of your sourdough starter and place it on top of some water, if the dough is full with gas it will float on top of the water. If it’s not ready, it can’t float and will sink to the bottom. This test does not work with every flour, rye flour for instance can’t retain the gas as well as wheat flour and thus in some cases will not float. That’s why I personally don’t use this test and can’t recommend it.

Once you see your starter is ready I would recommend giving it one last feeding and then you are ready to make your dough in the evening or the next day. For the instructions on how to make your first dough please refer to the next chapters (7 and 8) in this book.

If your first bread failed, chances are your fermentation hasn’t worked as expected. In many cases the reason is your sourdough starter. Maybe the balance of bacteria and yeast isn’t optimal yet. In that case a good solution is to keep feeding your starter once per day. With each feeding your starter becomes better at fermenting flour. The microbes will adapt more and more to the environment. Please also consider reading the stiff sourdough starter chapter in this book. The stiff sourdough starter helps to boost the yeast part of your sourdough and balance the fermentation.

3.4 Maintenance🔗

You have made your sourdough starter and your first bread. How do you perform maintenance for your starter? There are countless different maintenance methods out there. Some people go completely crazy about their starter and perform daily feedings of the starter. The key to understanding how to properly conduct maintenance is to understand what happens to your starter after you used it to make a dough. Whatever starter you have left, or a tiny piece of your bread dough can serve to make your next starter.4

As explained earlier your starter is adapted to fermenting flour. The microbes in your starter are very resilient. They block external pathogens and other microbes. That is the reason why, when buying a sourdough starter, you will preserve the original microbes. It is likely that they are not going to change in your starter. They are outcompeting other microbes when it comes to fermenting flour. Normally everything in nature starts to decompose after a while. However, the microbes of your starter have very strong defense mechanisms. In the end, your sourdough starter can be compared to pickled food. Pickled food has been shown to stay good for a very long period of time [1]. The acidity of your sourdough starter is quite toxic to other microbes. The yeast and bacteria though have adapted to living in the high-acid environment. Compare this to your stomach, the acidity neutralizes many possible pathogens. As long as your starter has sufficient food available it will outcompete other microbes. When the starter runs out of food the microbes will start to sporulate. They prepare for a period of no food and will then reactivate the moment new food is present. The spores are very resilient and can survive under extreme conditions. Scientists have claimed they found 250 million-year-old spores that are still active [51]. While being spores they are however more vulnerable to external pathogens such as mold. Under ideal conditions though the spores can survive for a long time.

But as long as they stay in the environment of your starter they live in a very protected environment. Other fungi and bacteria have a hard time decomposing your left over starter mass. I have seen only very few cases where the starter actually died. It is almost impossible to kill a starter.

What happens though is that the balance of yeast and bacteria changes in your starter. The bacteria is more fitted to living in an acidic environment. This is a problem when you make another dough. You want to have the proper balance of fluffiness and sour notes. When a starter has hibernated for a long period, chances are that you do not have a desirable balance of microbes. Furthermore, depending on the time your starter hibernated you might only have sporulated microbes left. So a couple of feedings will help to get your sourdough starter into the right shape again.

The following are a couple of scenarios that will help you to conduct proper starter maintenance, depending on when you want to bake the next time.

- I would like to bake again the next day:

-

Simply take whatever starter you have left and feed it again. If you depleted all your starter you can cut a piece of your dough. The dough itself is nothing different than a gigantic starter. I recommend a 1:5:5 ratio like mentioned before. So take 1 piece of starter, feed with 5 parts of flour and 5 parts of water. If it is very hot where you live, or if you want to make the bread around 24 hours later after your last feeding, change the ratio. In that case I would go for a 1:10:10 ratio. Sometimes I don’t have enough starter. Then I even use a ratio of 1:50:50 or 1:100:100. Depending on how much new flour you feed it takes longer for your starter to be ready again.

- I would like to take a break and bake next week:

-

Simply take your leftover starter and place it inside of your fridge. It will stay good for a very long period. The only thing I see happening is the surface drying out in the fridge. So I recommend drowning the starter in a little bit of water. This extra layer of water provides good protection from the top part drying out. As mold is aerobic it can not grow efficiently under water [15]. Before using the starter again simply either stir the liquid into the dough or drain it. If you drain the liquid you can use it to make a lacto-fermented hot sauce for instance.

The colder it is the longer you preserve a good balance of yeast and bacteria. Generally, the warmer it is the faster the fermentation process is, and the colder it is the slower the whole process becomes. Below 4 °C the starter fermentation almost completely stops. The fermentation speed at low temperatures depends on the strains of wild yeast and bacteria that you have cultivated.

- I would like to take a several months break:

-

Drying your starter might be the best option to preserve it in this case. As you remove humidity and food your microbes will sporulate. As there is no humidity the spores can resist other pathogens very well. A dried starter can be good for years.

Simply take your starter and mix it with flour. Try to crumble the starter as much as possible. Add more flour continuously until you notice that there is no moisture left. Place the flour starter in a dry place in your house. Let it dry out even more. If you have a dehydrator you can use this to speed up the process. Set it to around 30 °C and dry the starter for 12–20 hours. The next day your starter has dried out a bit. It is in a vulnerable state as there is still a bit of humidity left. Add some more flour to speed up the drying process. Repeat for another 2 days until you feel that there is no humidity left. This is important or else it might start to grow mold. Once this is done simply store the starter in an airtight container. Or you can proceed and freeze the dried starter. Both options work perfectly fine. Your sporulated starter is now waiting for your next feeding. If available you can add some silica bags to the container to further absorb excess moisture.

Initially, it would take about three days for my starter to become alive again after drying and reactivating it. If I do the same thing now my starter is sometimes ready after a single feeding. It seems that the microbes adapt. The ones that survive this shock become dominant subsequently.

So in conclusion the maintenance mode you choose depends on when you want to bake next. The goal of each new feeding is to make sure your starter has a desired balance of yeast and bacteria when making a dough. There is no need to provide your starter with daily feedings, unless it is not mature yet. In that case, each subsequent feeding will help to make your starter more adept at fermenting flour.

1This is my go to pizza dough recipe. In Napoli modern pizzerias would use fresh or dry yeast. However traditionally pizza has always been made with sourdough.

2Discarding starter when preparing a new batch can be frustrating. With experience, bread-making becomes more efficient, and excess discard is rarely produced. It is possible to prepare just the right amount of starter needed for bread dough. In fact, a fully depleted starter can even be revived using a small portion of bread dough. Any leftover discard, rich in spores, can also serve as a backup to create a new sourdough starter. Simply mix the discard with a little flour and water, and it will spring back to life. That is a great option if the starter was accidentally depleted. A practical approach is to store all discard in a single jar in the fridge, adding new discard on top as needed and using it whenever required.

3Whether this is working, I can’t scientifically say. Typically the microbes that have once taken place are very strong and won’t allow other microbes to enter. My starter has initially been made with rye flour. So chances are that the majority of my microorganisms are from a rye source.

4I very often use all my starter to make a dough. So if the recipe calls for 50 g of starter I make exactly 50 g starter in advance. This means I have no starter left. In that case I would proceed to take tiny bit of the dough at the end of the fermentation period. This piece I would use to regrow my starter again.